SciX Data Linking and Indexing part I. Data Holdings

Edwin Henneken (),

13 Jun 2024

One of the distinguishing features of the Science Explorer (SciX) is its integration of literature with research data, software, and services. SciX records accrue links to related research objects through curated text mining (finding citations and links to data and software in the publisher manuscript) and metadata enrichment (aggregating bibliographies maintained by missions and archives). Our work with community-led initiatives such as the Asclepias project and the Astrophysics Source Code Library have put ADS at the forefront of the FAIR efforts in the physical sciences. SciX extends these efforts to the remaining NASA Science disciplines.

Figure 1. The SciX holdings represented as a graph. The different shapes represent different resources (articles, data, software) and the different colored arrows represent relationships (like cites, supplements,...). Some of these links, like "record A cites record B" (e.g. the black arrows) only have meaning within SciX, because it is a relationship between two entities that only exist within SciX.

Before going into a discussion of how data products are linked to and indexed in SciX, we will first examine how data is represented in SciX itself.

By executing a query in SciX, users enter a nexus between scientists, research products (like publications) and a wealth of information these records are linked to, both internally and externally. SciX supports the discovery of high level science results and the evidence which they are built on.

The holdings of SciX can be represented as a graph, illustrated by figure 1. The nodes are digital objects, each representing research products (like journal articles, preprints, data products, software and multimedia presentations). The arrows represent relationships between the nodes; for example, an arrow can represent the relation “cites”, “is supplement to”, “is erratum for” or “is version of”. The blue circle represents the SciX holdings: everything within this circle has a representation in the SciX holdings in the form of a record, while everything outside this circle represents external information. The external information consists of digital objects that can be linked to SciX records by URIs. For example, a SciX record can have a link to a data product, hosted in an external repository, or to a document hosted elsewhere as supplementary information to an article in SciX. Linking can also happen in the other direction; for example, a platform like Wikipedia has many records with links to records in SciX.

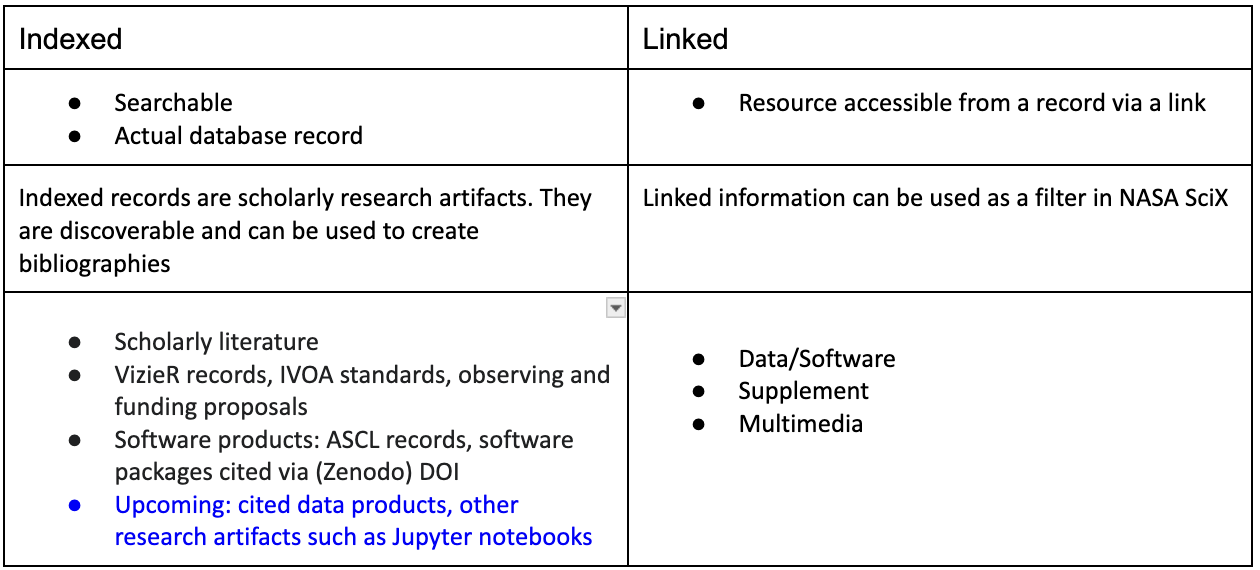

By construction links can, in principle, point to a resource outside of SciX, with the exception of two relationships that represent the following: “citations” and “co-readership”, both of which are only meaningful within SciX context. With this relation both the source and the target must correspond with nodes that lie within the circle in figure 1. The nodes within the circle represent what is indexed in SciX; these are actual, searchable database records, and their metrics (such as citations and reads) are tracked by SciX. Linked resources are not searchable, but they can provide a means for filtering search results. As an example, software packages cited in the literature are indexed records, which means you can use a SciX search to find all packages written by a particular researcher or cited more than N times. On the other hand, data products hosted by NASA archives are linked resources. While you can’t discover them with a search, you can find all the SciX records which link to one or more data products hosted by a particular archive such as MAST, Chandra, or SIMBAD. Table 1 summarizes the differences between indexed and linked information in SciX.

Table 1: Highlights of differences between what is indexed versus what is linked to in SciX.

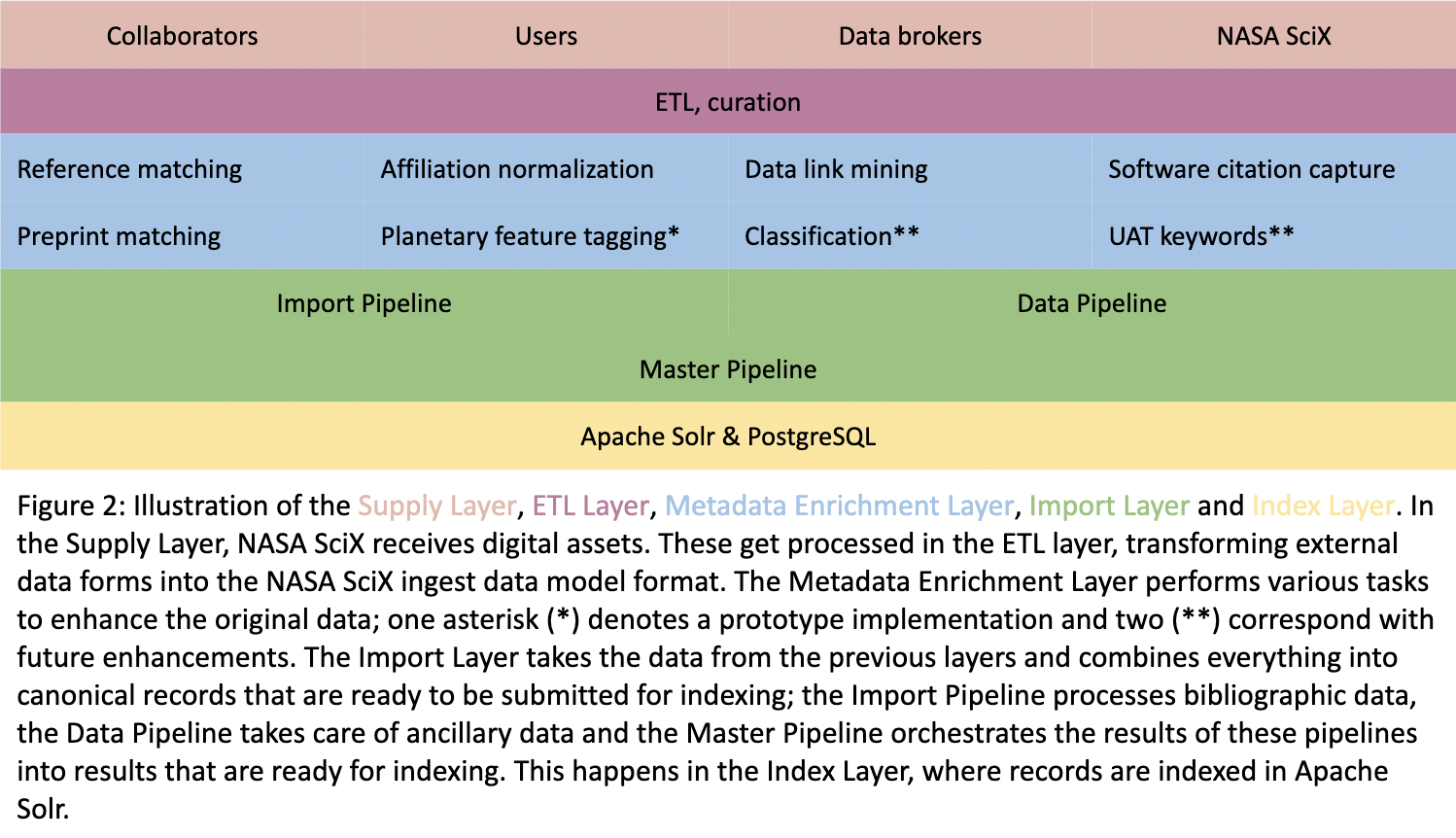

The SciX curation team receives digital assets (metadata, fulltext, relational data) from a range of sources and in a great variety of formats (ranging from simple ASCII text to highly structured XML data). These sources consist of collaborators (publishers, repositories, societies), users (missing publications, corrections, associations), other sources (mostly Crossref and DataCite) and SciX itself (even though internal, curated records are still a form of data supply, from a workflow perspective). These assets contain information that, down the line, need to become discoverable through the SciX user interface; to make this possible, we need an intricate process of extracting all the necessary elements from the original assets and putting them into a form that can be processed further. This workflow is made possible by format-specific parsers and the SciX ingest data model. Since data is often not perfectly formatted, the curation process in the ETL layer needs to be able to deal with all kinds of issues.

The augmentation layer enriches the original data with all kinds of information. In addition to making publications discoverable, SciX also maintains a citation graph. This graph is the result of the reference matching software in the augmentation layer; this framework takes reference data, either supplied or extracted, and attempts to match these to existing SciX records. The affiliation pipeline normalizes affiliations into canonical formats (see this blog). The mining of data links will be discussed in part II of this series. The software citation capture was discussed in this blog. The preprint matching process (called “docmatching”) is highlighted in this blog. We are developing a process that tags publications with planetary feature names, taken from the USGS Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature (see this publication). Future augmentations will include a pipeline that will assign publications to one of the disciplines represented in SciX (document classifier) and a pipeline that will assign terms from the Unified Astronomy Thesaurus (UAT tagger), whenever possible.

At this point, we have a lot of curated and augmented data, stored in various places. The next layer contains processes that consolidate all related assets into one canonical data unit, ready to be consumed by the indexing process. One service that SciX offers is the merging of preprint records with their associated published article records; the docmatching process identifies these correspondences and the import layer takes care of the record merging. Sometimes we receive metadata for one publication from multiple sources; the import layer takes care of merging these records according to specific rules. The final step in the Import Layer is the Master Pipeline orchestrating the merging of all these disparate data assets into a form that can be ingested and indexed in the final layer.

Finally, a couple of words about the general philosophy behind SciX. SciX is primarily a literature database, and as such it does not aim to be an index for all digital assets generated in scholarly research (like data products and software). However, one of the goals in SciX is to make those digital assets relevant that are discoverable from the literature, whenever feasible, for example when they are cited. In the next two parts of this blog we focus on one particular class of these digital assets: data products.

Science Explorer

Science Explorer